Menu | History | Monastic Period | Site Map | Search | Contact | Copyright

From cloister to

nature's sanctuary:

Notes on my spiritual journey - Roman Verostko, 2015

“We need the tonic of wildness . . .We need to witness our own limits transgressed”

- quoted from Henry David Thoreau, Walden

Pond, 1854

O n June 25th 1950, about 9 months after I graduated from the Art Institute of Pittsburgh, the U.S. was drawn into the war with North Korea and I was of draft age. The tragedies of World War II were still vivid in my mind, especially that of my older brother George who was burned to death when his half track was blown up in Germany in the last throes of World War II. I witnessed the depth of my mother's grief, her moaning and wailing when she received the telegram announcing his death. I also felt her pain and the silent unspeakable pain my father buried within himself. Seeing the deep hurt of killing and being killed in war, I could not imagine myself ever being a soldier. My teenage experience of the war lingered in my conscience like a deep festering sore and, I knew in my heart, that. I would never be able to fight; I would never carry a gun. This made monastic life all the more attractive.

Through the influence of another older brother, Bernard, I began reading about the history of western monasticism. We shared a lot of our mutual experiences during my art school days. About the time I graduated from Art School he was in the process of entering the monastery at St. Vincent Archabbey, a monastic life that seemed distant from anything I would ever undertake.

"The Decision

Bit", oil

painting on canvas, 1951,

(click

for full view)

My weekend visits with him at the St Vincent monastery deepened my interest. In addition, it was Thomas Merton's popular Seven Storey Mountain that captured my imagination and drew me more deeply into romantic notions of a cloistered life. On my 21st Birthday, September 12,1950, I entered a scholastic program at St. Vincent as my first step to becoming a fully committed Benedictine monk and, eventually, a priest. In my first year as a postulant I felt like this was not the right place for me. But I continued anyway. My interest in monasticism intensified as I learned more about Benedictine traditions associated with art and spirituality. The painting above was made during the time when I pondered whether I could or would make the leap to take vows and enter my Novitiate year. I entered the Novitiate in 1952.

|

Thomas Merton as a Cistercian Monk (1915–1968). His autobiography, Seven Story Mountain, first published in 1948 sold over 600,000 hard cover copies. Several colleagues, who were about my age who had entered monastic life with me had also been influenced by Merton's book. This increase in vocations suggests that our experience of WW II, the war in Korea and anxiety over the emerging cold war had set the climate for this surge. |

Those years were filled with enthusiasm enriched with the study of language, philosophy, theology and spirituality. None of these studies ever settled definitively all the questions I had pertaining to my experience of my "believing self". Underneath my commitment there remained unanswerable questions. Yet those questions faded in the presence of the learning and spirituality of older monks who were my mentors & teachers. . This was especially true of the Fathers Demetrius Dumm, Ildephonse Wortman and Quintan Schaut. Their depth of experience, breadth of knowledge and peaceful demeanor drew me deeper into the life. Yet, in hindsight, I wonder if I wasn't, from the beginning, on an inevitable course that would lead me eventually to leave this way of life.

|

Crucifix. clay & painted wood I created this work while I was in residence at St. Michael's Rectory on West 34th St. in New York where I had a studio space. The Archabbot had sent me to NY to pursue further studies in art history, theory and practice. |

The crucifix above exemplifies the marriage of my life and my art during my monastic period. This work presents a twisted form fashioned in red clay mounted on a cross. The twisted clay is intended to be expressive of an "agonizing" physical experience.. The cross, painted white with colorful geometric forms complements the form it supports. Human suffering is represented by the clay form while the white cross with colorful geometry stands for transformation and resurrecxtion. The process of human suffering is viewed as a process of transformation, the passageway to the fullness of life. My 1960's "New City" paintings symbolized human passion and transformation in a similar way. Those works grew from a view of our life's journey as a transforming process through the "vale of tears" to the "New City", the New Jerusalem, the promised land, the fullness of life beyond the body-life experience on earth. These works could be viewed as visualizations of "things hoped for".

|

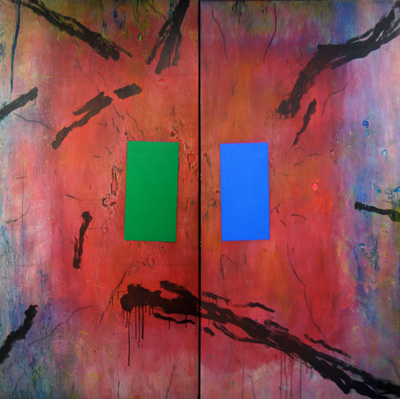

The New City Grows, 1967.

( 8 ft by 8 ft, two 4 by 8

ft panels joined.). Crayon and acrylic on plywood primed

with white gesso. .. Spontaneously drawn crayon markings & brushwork on large stained fields share the same picture space with carefully sized geometric forms. The marriage of these form-oppositions, calculated form and spontaneous gesture, represented my belief, at that time, in life's journey as a transforming process that ultimately resolves conflict and suffering in the New City, the New Jerusalem. Click on image for large details The concepts underlying this work, reflect the influence of Teilhard's view of human evolution as an evolving mystical body . -- Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, The Phenomenon of Man. 1955. |

Between 1963 and 1968 my art work became increasingly involved with visual oppositions that complemented and created each other in a visual dialectic. The visual dialectic in my art work echoed my personal struggle to reconcile the believable and the unbelievable in my spiritual life. I kept these private struggles with personal faith separate from my ministerial work and continued to live my monastic life. At some point of time in my Washington years I had come to realize that I could not continue my clerical and monastic life without resolving this conflict.

By 1967, with encouragement from Stephen Joy, my friend and art critic, I began experimenting with emerging new media with a focus on electronics. This interest led me to create electronically synchronized audio-visual programs featuring projection of evocative texts with drawings & images and sound tracks. The "Psalms in Sound and Image" featured nature and attempted to magnify the "marvelous" mystery of commonplace experience. The last of those Psalms, the Psalm of Love, magnified "love for the other" that is essentially the Golden Rule. Above all else, the Psalms were a strong affirmation of ordinary life and our relationship to the earth. They draw on the commonplace experience of life as a transforming process.

| Slides from the "Psalms in Sound & Image", a series of synchronized audio visual programs dating from 1967. | |

The resolution of my conflict took place in the last months of 1967 and the first weeks of 1968 . In January, following a lecture tour with my "Psalms in Sound & Image" I found the path I would follow. I would leave the monastery. I could not continue to present myself as a person adhering to or professing beliefs or teachings that were problematic for myself. This pathway could be likened to a two edged sword: on the one hand it severed the burden of doctrines and teachings that were deeply troubling for me ; it also took me away from a community of caring colleagues whose learning and wisdom supported my learning and enriched my life. The departure process made me more aware of the value of community and my own limitations.

Although I stood on the threshold of the unknown I also experienced a freedom to explore alternative spiritual paths. Unwieldy doctrines that weighed heavily on me for decades were lifted. The binding force of creeds faded and my ability to affirm life grew. This experience would lead me more deeply into nature's sanctuary for renewal.

|

The Tarantula Nebula. See the entire Hubble Gallery:

http://hubblesite.org/gallery/album/entire Credit: NASA, ESA, ESO, D. Lennon (ESA/STScI), and the Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA) |

This experience was strengthened by my friendship with Alice Wagstaff who chaired the graduate school of Psychology at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh. We had met in 1967 when she was invited to conduct a seminar for Deacons on "client-centered" therapy at our St. Vincent Seminary. Our friendship grew via correspondence, shared cultural events in Pittsburgh and eventually meetings whenever we could find occasions to meet. As our relationship passed the threshold of casual friendship the option for a radical change of life turned into practical plans to get married. I left my monastic life at the end of the academic year in 1968 and I joined the Humanities Faculty at the Minneapolis School of Art, now known as the MCAD (Minneapolis College of Art & Design). I spent most of the summer in a log cabin near Farmington, Pennsylvania preparing coursework and planning a new life with Alice. We were married on August 11th, 1968, in Pittsburgh and moved, one week later, to Minneapolis.

|

| My wife, Alice Wagstaff, March 25, 2004, Oregon. Alice's love and knowledge of nature enriched both our spiritual and physical life. In the spring of 2004, along this mountain stream she was drawn to this tree and embraced it silently for several minutes. She then turned and smiled for this picture. We foraged for some spring greens along the way. Through her I learned that this was sacred ground to be approached with quiet reverence. She also talked to her plants in a serious way. Occasionally she would salvage a dying plant, trim the dead parts, enrich the soil, and encourage it to recover. She assured me that she did indeed communicate with some plants. |

Leaving the monastery turned out to be an enriching experience for both of us. We found sanctuary via the people in our lives and the richness of regional Nature Centers. Alice taught me to pay attention to "other life" and our dependence on life "other" than human life for our own survival. My mind embraced the freedom to explore and ask questions without having to reconcile answers to fit inherited beliefs. And it turned out to be OK to embrace the mystery of life without having an answer.

|

|

Woodlake Nature Sanctuary, Richfield, MN . Our favorite sanctuary, close to home, had pathways through woodland, and prairie with a boardwalk over a lowland lake with waterplants and wildlife. |

Regional nature preserves became our sanctuary for meditation and reflection. Coupled with the study of world cultures these meditations nurtured a growing interest in our human relationship to nature and ecological ethics. For me our nature preserves emerged as precious "sanctuaries" of our time, cathedrals nurturing and preserving life. This experience led me to introduce a section on "Ecological Ethics for Artists" in my seminar for graduating seniors.

|

|

Alice at the entrance to the Peace Garden, Minneapolis, Spring 2001 |

Through these sanctuaries the mystery of life and the immensity of cosmos invaded my consciousness drawing me ever more deeply into the awesome mystery of life and being alive. This heightened my experience of "being here", awakening me to the binding interconnections to each other and our dependence on the myriad forms of other life and the health of our mother earth. This experience has charged me with spiritual strength, peace, and acceptance of my human limits. It has brought me to embrace life more fully and to stand without any fear of the unknown.

|

| This Peace Garden was one of Alice's favorites. I took her there in her wheelchair often in the spring and summer of her last year. |

Gradually I came to experience Peace with myself. Yes, I can truly share the monastic greeting I learned as a monk at St. Vincent Archabbey, "Peace be with you", Pax Tecum.

Roman , Minneapolis 2006 ff.

Main Menu | History | Monastic Period | Site Map | Search | Contact | Copyright